How the New Image of Our Galaxy's Black Hole Helps Us Understand a Life of Faith

Sermon Delivered at The Local Church

May 15, 2022 • Easter 5C

Scripture: Acts 11:1-18

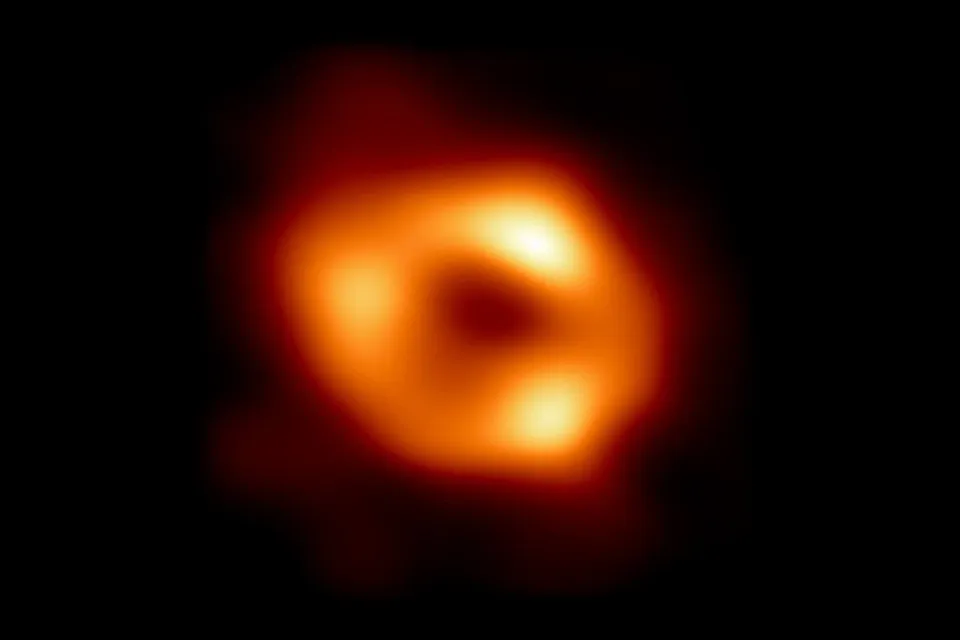

Earlier this week, I got a breaking news alert on my phone with this picture. It’s called Sagittarius A-star, and it’s our galaxy’s black hole. I’m not cut out to fully explain what a black hole is, but what I have learned this week is that black holes were predicted by Albert Einstein when he introduced his theory of relativity, and what we know is that a black hole is an area in space where the gravity is pulling so much that it can bend light, warp space, and distort time. There’s so much gravity, so much force, that no light can escape it. That’s why it’s called a black hole.

And this one in particular, Sagittarius A-star, sits in the center of the Milky Way galaxy. Every galaxy has a black hole at the center. What you’re seeing here is the first-ever image of ours, revealed by scientists around the world this week — the product of 300 researchers at 80 institutions who all worked together to create a global network of eleven telescopes to assemble this one image. This is a big deal in astronomy. There’s only been one other image of a black hole — one that’s outside of our galaxy, 55 million light-years away, taken about three years ago. But this one is much closer, only about 27,000 light-years away.

And it’s a big deal not only because of what this image could teach scientists and astronomers and researchers about the physics of black holes and of space and even the cosmic origins of our own universe, but it’s also a big deal because an image like this had been elusive for quite some time. Because black holes are such that no light can escape, getting a picture of our own was thought to be near impossible — until now. In fact, this is what I found so fascinating (maybe because this was the part I could actually understand).

But scientists have been working on getting an image like this since 1967 when a physicist named James Bardeen hypothesized that a black hole could be visible. He even correctly predicted that it would look something like this. And ever since then, astronomers and physicists have been working to figure out how to make the invisible visible. They’ve been working to make concrete what they only knew to be abstract. They’ve been working to fine-tune their measurements, adjust their wavelengths, and all of the things to try to bring this image into focus.

That’s why this is a big deal. But even now, as you can see, the image of Sagittarius A-star isn’t very clear. In some ways that’s because of the nature of the black hole — there is gas around the black hole that’s moving so fast, it’s hard to get a clear shot. One scientist who worked on this project said, that it was “a bit like trying to take a clear picture of a puppy quickly chasing its tail.” And this gives them their challenge going forward. They’re going to continue to fine-tune and test and adjust to continue to seek a clearer picture. Their next goal is apparently trying to capture a moving image with much greater clarity. This is a great first step.

And believe it or not, this all brings me to Peter.

Just like last week, the passage today is again from the Acts of the Apostles. And as I mentioned last week, Acts is essentially the sequel to Luke’s gospel in the New Testament — the story of God and God’s people once Jesus has burst onto the scene. It tells the story of Jesus’ friends and followers after his ascension to the Father and the descending of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost and narrates how that Spirit acts in their lives and in the lives of those they encounter. I mentioned this last week, but as one friend put it, Acts tells the story of a people trying to assemble a bike while riding it. I love that image. It’s sort of like starting a church.

So we meet Peter who has just returned to Jerusalem from Joppa. If you remember, Joppa was where Peter had raised Tabitha from the dead which we heard last week. And he ends up staying there for a little while. And while he’s there, he has this incredible experience which he is now relaying back in Jerusalem.

You heard it read, but it’s worth hearing again. Peter describes how he was on a rooftop in Joppa praying when all of a sudden he becomes entranced and has this vision of a sheet that comes down from heaven. I like to call it a holy sheet… But anyway, on this sheet, there are all kinds of animals — four-footed creatures and reptiles and birds. And if that’s not strange enough, he hears a voice that says, “Get up, Peter; kill and eat.” But Peter responds, “By no means, Lord, for nothing profane or unclean has ever entered my mouth.” But the voice replies, “What God has made clean, you must not call profane.”This whole exchange happened three times at which point everything is taken up again into heaven.

No sooner had this holy sheet disappeared than there was a knock at the door. A centurion named Cornelius had been told in his own vision to send for Peter, and so there are some men at the door who’ve come to take him to back to Caesarea with them. The Spirit tells Peter to go with them, and so he does, and when they all arrive, they enter the house of Cornelius. And as Peter begins to speak there, the Holy Spirit falls on them, and they’re baptized and welcomed into the family of God.

And now, what you need to know is that those who’ve gathered to listen to Peter tell about his encounter aren’t just there for a trip report. They’re not there to drink wine and watch a slideshow of Peter’s travel. They’re there with some tough questions for Peter. And that’s because these here in Jerusalem are Jewish followers of Jesus. We know this because Luke refers to them as circumcised believers. To be circumcised is essentially to be marked by God in a physical way and thus marked as a part of God’s chosen people. And it also means that, as a Jew, you’re expected to adhere to certain Jewish purity laws — like what animals you can and can’t eat or who you can eat with. All of these rules and customs and laws aren’t necessarily there for their own sake. They’re not there for legalistic reasons only; rather, they’re meant to instead maintain the integrity of the faith. These customs give their Jewish faith a certain standing. The laws and rituals have helped to give them their identity as the people of God — as Israel.

Gentiles, a term for those who weren’t Jewish, were not circumcised and thus to this point not considered part of God’s family. They were considered outsiders.

Peter was a Jewish follower of Jesus, and that would mean not only that he was circumcised, but also that he was expected to adhere to these laws. And the Jewish followers of Jesus there in Judea had heard how Peter had entered Cornelius’ house, a Gentile, and ate with them — he’d shared a table with other Gentiles — and so he had thus betrayed their sacred covenant and broken their law. And they want to know why. And underneath this question are other questions — serious questions with high stakes.

I think sometimes when we hear stories like this, we have a tendency to oversimplify the conflict. We reduce it to simply choosing sides or trying to determine who’s right and who’s wrong. But if we listen closely, we actually hear echoes of these questions in the questions that are still asked today. What those with Peter really want to know is if fellowship with Gentiles would weaken the faith. Would it weaken their commitment to the faith? Would it somehow compromise what they believed? Ultimately, would too much mixing result in their faith and thus their identity being lost? Would this impurity begin a slippery slope of becoming scattered to nothingness? Would it be the beginning of the end of God’s people?

Peter would have carried these same questions, too. Because this would have thrown everything Peter thought he knew into flux. He would’ve realized that this whole experience is pointing to a new reality. Because he would have begun to see that this experience wasn’t necessarily about animals or food, but about people — ones who have been labeled profane but who God calls good. It would have been a moment of crisis for him as this experience with the sheet and the voice and the visit to Cornelius and the table fellowship — all at the Spirit’s leading — it all slams against everything he’s ever known. Everything he’s ever been taught. The life he’s lived. His entire worldview and moral ethic to this point.

It’s a crisis of faith, and Peter is faced with a seemingly impossible task: How do you reconcile a faith you’ve known with a faith that is becoming known? How do you reconcile the seen with the unseen? In other words, how do you hold on to that which has given you grounding and identity your whole life while at the same time you can’t shake the feeling that God is telling you to do something new that just happens to also be the complete opposite? What do you do when the word of God flies in the face of… the word of God?

Peter does the only thing he can do in that moment. He tells his story. He tells them about the sheet and the animals and about how what God has made clean we shouldn’t call profane. He describes the visit to Cornelius’ house and the meal and his preaching and how the Spirit fell and how they were all baptized. And at the end, it’s as if Peter says, “Look, y’all, I get it. But this isn’t a question for me. You got to take it up with the Holy Spirit. I can’t explain it. I can only tell you what I’ve experienced — that we were better together. That nothing was compromised; in fact, it was enriched and enhanced and more beautiful than we could ever imagine. That God showed up big time, y’all, and is doing something new. That they’re part of the family now. If then God gave them the same gift that he gave us when we believed in the Lord Jesus Christ, who was I that I could hinder God?” In other words, “Who am I to stand in the way of what God is already doing?”

This was Peter’s mic drop moment. And after he said this, they praised God. They celebrated. They were made new. This was their resurrection moment.

There are so many things I love about this story. I love that question. Who am I to stand in God’s way? I wonder how often we do that when we cling so tightly to customs and traditions and rules and beliefs that we fail to err on the side of love and compassion and grace. That we inhibit the new thing that God might be doing.

I also love that Peter doesn’t come back at them with a well-formulated argument and a bunch of PowerPoint slides about Gentile inclusion. Instead, he simply shares his story — what helped him see that it wasn’t about rules or customs or animals or food but about people. And it’s his testimony — his lived experience — that moved him from the abstract to the particular, from the hypothetical to the human, that changes their hearts and minds and reorients them to the work of the Spirit and helps them see what they couldn’t before. And they can’t argue with his story.

And I love that Peter doesn’t wait to move in the direction of love until he’s figured it all out. When the Spirit tells him to eat or go to Cornelius’ home, he doesn’t shrink back and default to old patterns. In the same way, he doesn’t go home and double down on his certainty, pulling out those passages from the Hebrew Bible that would simply reinforce what he’s always believed. Instead, he simply says yes to God and opens himself to the Holy Spirit — to the presence and power of God, perhaps remembering his experience with Jesus — who he ate with, who he touched, who he healed, and how he lived, died, and lives again — with arms outstretched for the world. He didn’t hesitate. He just said yes.

It’s this “yes” creating a pathway to a new experience that has brought substantive positive change to the Church. In the 18th century, John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist movement, was among the earliest to allow women to preach in the church for this very reason — because of how he and others experienced the Spirit moving in and through their preaching. He essentially said, “Who am I to stand in God’s way?” That risk-taking, tradition-defying yes made way for something new. I wouldn’t be in ministry today if it weren’t for the preaching of women.

There are similar questions raised now in many Christian circles about the inclusion of queer persons. Should they be ordained? Should they be married? Here at The Local Church, inclusivity is one of our core values, and we affirm the sacred worth, belonging, and full participation of all persons — period. But part of being an inclusive community is also recognizing that people may be at different places having been taught different things.

I remember sharing a meal with someone a few years ago who was working this out — something I’m always happy to do if you have similar questions. And this person had grown up taught that being gay was a sin. He had all the scripture to back it up and could recall it with ease. And for him, like the Jewish followers of Jesus there in Jerusalem, what was at stake was his identity and foundation. He found himself at a similar crossroads as Peter. And as we were talking about LGBTQ inclusion, and I was sharing my story of how I got to where I am as an affirming pastor, I remember he said to me, “I’m just not there yet.”

And I said, “Ah… good. Because that means you’re moving. And it means God’s not done. It means you’re on the way.”

Do you remember this picture? Maybe you’ve long hypothesized that something is there, but you just couldn’t yet see it. Or maybe today you’re seeing something new and, even if you can’t explain it fully, it’s still breathtaking. Maybe for you, the image could still stand to be clearer, and so you continue to test and adjust, working to bring it into sharper focus.

This is the life that Peter embodies. A life of faith is all about evolution. And what Peter demonstrates is not to be afraid of that evolution but to embrace it — because we’re all better for it. In the words of St. Anselm, it’s a faith seeking understanding. Saying “yes” to the Spirit is like fine-tuning measurements and adjusting wavelengths until the picture becomes clearer — and the whole world is made new again.

Just try to stay out of God’s way.